The greatest joy of working in oils is the freedom the medium gives the painter to work large, small, detailed or loose, translucent or opaque; no other medium offers so many options for expression and is so easy to get to a working competence with. This is quite a straightforward oil painting – I’ve kept the finish of it relatively simple so that you can try it at home.

The support I’ve chosen is a 30 x 40 inch canvas. Working on this scale gives me the opportunity to work boldly and freely and is a great way to force oneself away from over-detailing or being fussy – for those reasons I urge you to work on a similar support, aiming to finish the oil in two or three morning or afternoon sessions.

Rather than slavishly record how I painted this in a step by step manner, I want to focus on broader principles that will be more of use to you in learning oils.

First of all think about the progression of the painting, how will it develop, and how can you break that development into stages?

My first stage is the imprimatura or underpainting. We teach a number of ways of approaching imprimaturas, but for this one I use Turner’s preferred method of a fairly bright imprimatura that roughly accords with what we’ll paint over it; Turner called these ‘colour beginnings’. As I’ll be working straight over this, I simply wash in paint diluted with turpentine (not medium) and let it dry for 10 minutes while I have a cup of tea. Once I have a base colour I think about laying in the foundations of the picture, in large, simple blocks of colour.

My first stage is the imprimatura or underpainting. We teach a number of ways of approaching imprimaturas, but for this one I use Turner’s preferred method of a fairly bright imprimatura that roughly accords with what we’ll paint over it; Turner called these ‘colour beginnings’. As I’ll be working straight over this, I simply wash in paint diluted with turpentine (not medium) and let it dry for 10 minutes while I have a cup of tea. Once I have a base colour I think about laying in the foundations of the picture, in large, simple blocks of colour.

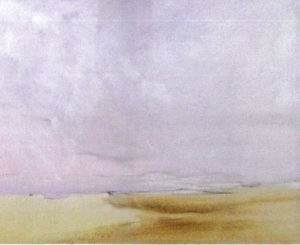

I work over the dry imprimatura with large brushes and medium thinned oil paint to roughly indicate the main elements of the painting. Working thinly and rapidly, there is no need to worry about details at all yet. It’s extremely important to control the translucency of the underpainting, too much opacity will kill the underlying luminosity created by the imprimatura, and too little will make the picture look weak and disjointed. One of the tips we teach here is to use paper towels as well as brushes to wipe back paint, soften edges and recover translucency; Turner famously even used his muffler to dab at his paints as he worked! At this stage any underpainting lacks three things; atmospheric depth, modelling and details, so I decide to let it dry before I push on; if you mix a fast drying medium it can be workable in about 8-12 hours. The theory of creating depth in a painting is straightforward; the support is flat, the world isn’t – so one has to trick the viewers eye into believing things are otherwise. If you paint slavishly from photographs you’ll always fail to do this well as the colours recorded by lens are not the same as you’ll need to create the illusion of depth.The illusion of atmospheric depth is created by placing cool subtler colours in the distance and warm, more saturated ones closer to the viewer, and a camera will never create this sequence for you.

First I knock back the horizon area by glazing in a translucent mix of white with a little blue; this effectively de-saturates that passage of paint making it appear to recede relative to the mid and foregrounds.Secondly I warm and darken the foreground with a glaze of warm earth colours (I use Burnt Umber). This creates the illusion of advancing the foreground, in relation to the mid ground and increases the relative recession of the horizon.Next do the same with the sky, advancing bits, receding bits, or adding general areas of translucent colour and light. I deaden down a few bits of the imprimatura further and put a bit of rain in over the distant headland. Because I worked with a medium extended with a little oil I am able to work straight through to do a bit of modelling on top of the layers I just painted. If you have painted glazes previously you have probably noticed how the colours you created appeared ‘deep’ and complex compared to straight oil paint. This is the phenomenon of ‘optical mixing’ and the key to most of the Old Masters techniques; unfortunately it’s beyond the scope of this article to explain it in depth. For now just be aware that any fresh paint you put on while the support is wet will not have great optical depth, but will be simple wet on wet direct paint.

First I knock back the horizon area by glazing in a translucent mix of white with a little blue; this effectively de-saturates that passage of paint making it appear to recede relative to the mid and foregrounds.Secondly I warm and darken the foreground with a glaze of warm earth colours (I use Burnt Umber). This creates the illusion of advancing the foreground, in relation to the mid ground and increases the relative recession of the horizon.Next do the same with the sky, advancing bits, receding bits, or adding general areas of translucent colour and light. I deaden down a few bits of the imprimatura further and put a bit of rain in over the distant headland. Because I worked with a medium extended with a little oil I am able to work straight through to do a bit of modelling on top of the layers I just painted. If you have painted glazes previously you have probably noticed how the colours you created appeared ‘deep’ and complex compared to straight oil paint. This is the phenomenon of ‘optical mixing’ and the key to most of the Old Masters techniques; unfortunately it’s beyond the scope of this article to explain it in depth. For now just be aware that any fresh paint you put on while the support is wet will not have great optical depth, but will be simple wet on wet direct paint.

Next, using Filberts, I work on the basic underpainting to create the illusion of three-dimensional-light scheme for each shape I soon create a fairly finished looking oil, although these ‘tone sequences’ as they are called can get extremely complex; Rembrandt for example had a very elaborate one that incorportated variances not simply in tone, but also colour temperature, paint thickness and even the rough/smooth finish of the paint.

Next, using Filberts, I work on the basic underpainting to create the illusion of three-dimensional-light scheme for each shape I soon create a fairly finished looking oil, although these ‘tone sequences’ as they are called can get extremely complex; Rembrandt for example had a very elaborate one that incorportated variances not simply in tone, but also colour temperature, paint thickness and even the rough/smooth finish of the paint.

Next I model the clouds a bit, sharpening the edges here, losing them there, and develop both the atmospheric perspective and principal shades in the landscape.

Next I model the clouds a bit, sharpening the edges here, losing them there, and develop both the atmospheric perspective and principal shades in the landscape.

Lastly I decide I need to ‘push’ the scene a bit to create more drama, and to do this I simply play around with the effects of light; creating a more brooding intensity to the storm, a ‘spotlit’ focal point, and drop in a few suggestions of detail – including a traditional red Norfolk sail in the focal area to catch the viewers eye.

Lastly I decide I need to ‘push’ the scene a bit to create more drama, and to do this I simply play around with the effects of light; creating a more brooding intensity to the storm, a ‘spotlit’ focal point, and drop in a few suggestions of detail – including a traditional red Norfolk sail in the focal area to catch the viewers eye.

On balance I think this little oil has turned out reasonably well; it’s brooding atmospheric and has lots of character. As I painted the later stages I strayed further and further from the source; I always advocate painting away from the source and towards one’s concept. Painting needs to communicate ones’ feelings about the subject or it’s just an inefficient way of making inaccurate copies of photographs!

If you like to see more of Martin’s work, please visit his website: makinnear.com/

Love what you’re reading? Join the SAA to unlock even more benefits! As a member, you’ll gain access to exclusive step-by-step tutorials and videos, discounts on art supplies, and inspiring competitions. Plus, receive your subscription to Paint & Create magazine and join a vibrant community of fellow artists. Don’t miss out—become a member today!