Going to London for the day is always exciting, but this time was extra special for me, as I was going to see something that I had hoped to see since I first heard about it in 2018.

“What is it?”, I hear you cry – well, it is the David Hockney window in Westminster Abbey. Ever since seeing the BBC documentary about the making of the window, this went straight on my bucket list.

When you arrive at Westminster Abbey you can’t help but be impressed by this magnificent building, with its huge flying buttresses supporting its massive walls. As soon as you step inside you are reminded that you are walking in the steps of more than 1000 years of history.

When you arrive at Westminster Abbey you can’t help but be impressed by this magnificent building, with its huge flying buttresses supporting its massive walls. As soon as you step inside you are reminded that you are walking in the steps of more than 1000 years of history.

In the 1040s King Edward (later Edward the confessor) enlarged a small Benedictine monastery close to his royal palace on the banks of the river Thames. He did this by having a large stone Church built in honour of St Peter the Apostle, which became known as Westminster distinguishing it from St Paul’s Cathedral in the east, or Eastminster. King Edward died only a few days after the new church was consecrated, and his remains were entombed in front of the High Altar. The abbey has been the setting for every coronation since the first documented coronation in 1066, of William the Conqueror. Since then, there have been coronations for 40 reigning monarchs!

The age of cathedral building ensued, and in the 13th century King Henry III rebuilt the church in the popular gothic style of the time. Building continued over the centuries making it the magnificent building it is today.

The visitor entrance is currently situated in the north transept where you are immediately presented with the newest addition to the abbey – a celebratory stained-glass window, which is framed on either side by more traditional figurative story windows. Portraying a contemporary landscape in vibrant, vivid colours designed by one of the greatest British artists of the 20th century, David Hockney. Revealed in Sept 2018, to celebrate the reign of Queen Elizabeth II and known as the Queen’s window, it measures 8.5 metres high by 3.5 metres wide and was previously a clear glass window. Not afraid to try different mediums and styles, this was Hockney’s first work in stained glass and was designed digitally using an iPad.

The visitor entrance is currently situated in the north transept where you are immediately presented with the newest addition to the abbey – a celebratory stained-glass window, which is framed on either side by more traditional figurative story windows. Portraying a contemporary landscape in vibrant, vivid colours designed by one of the greatest British artists of the 20th century, David Hockney. Revealed in Sept 2018, to celebrate the reign of Queen Elizabeth II and known as the Queen’s window, it measures 8.5 metres high by 3.5 metres wide and was previously a clear glass window. Not afraid to try different mediums and styles, this was Hockney’s first work in stained glass and was designed digitally using an iPad.

The initial brief given to Hockney by Reverend John Hall, dean of Westminster Abbey, was to create a symbolic representation of a subject that would be recognisable as a David Hockney piece and not figurative or heraldic, like many of the existing stained-glass windows in the abbey. The response by Hockney was to create a vivid, stylised country scene with hawthorn blossom, depicted in circular shapes scattered over brightly coloured bushes and trees. The bold colours of red, yellow, orange, blue, green, and pink are utilised to represent the countryside of his beloved Yorkshire, where the artist was born in 1937.

In an interview Hockney describes the circular blossom as though champagne has been poured over the bushes, which is a perfect description. The window is a mastery of colour from the red path which leads you into the design surrounded by stylised hawthorn bushes in complementary hues of green. Pink shadows creep across the path whilst taller trees and branches stand proud in bright yellow. Then, across the whole of the image come circular pops of blossom in white, pinks, light blues and red, scattered across the bushes and trees in random patterns. The circular style of the hawthorn blossom can be seen in earlier works by Hockney, such as the Big Hawthorn (2008).

The main window design is set in two arches, with a narrow central column (mullion) through the middle to support the window. The window consists of 22 panels, supported by bars set into pockets in the stonework, and topped by an eyelet with 6 more circles radiating from the central circle. The colours change during the day and over the year, depending on the light outside and the position of the sun.

Unlike most other stained-glass windows in the abbey, this window is not painted, apart from the artist’s hand-painted signature in the bottom right corner. The glass used for the window was made using traditional hand blowing techniques by Glashütte Lamberts glassworks in Bavaria. Directors of the Barley Studio, Keith Barley and Helen Whittaker, and a team of expert stained-glass artists created the beautiful glass. Barley Studio has been a leading stained-glass studio for over 40 years now. The staff are passionate about conservation, restoration and creating new glass works for churches, homes, and schools based in York.

Working closely with the artist, and using traditional methods helped to bring the window to life. The window was assembled piece by piece, like a giant, intricate jigsaw puzzle. This was not the first piece that the studio had created and installed in the abbey, there are several windows by this studio currently in the abbey, including in the Lady Chapel, known as the Marian Windows. These contemporary pair of windows, from painted design by Hughie O’Donoghue RA and measuring 25 feet tall and ten feet wide, are resplendent in blue, with colour and symbolism representing the Blessed Virgin Mary as part of the 60th anniversary of the Queen’s coronation in June 2013. These frame either side the magnificent Battle of Britain memorial window, designed by Hugh Easton in 1947, and the central east window by Alan Younger installed in 2000. Many of the windows in these areas were damaged during the Blitz of the second world war in the 1940s, and the clear glass windows are now being replaced with decorative stained glass.

Walking through the abbey, every turn you are surrounded by beauty and artistic brilliance. Remember to look up as well as down as the high vaulted ceilings frame the magnificence of the structure. Oh, and the sculptures! I am in total awe of how stone can be sculpted into fine delicate figures and fine drapery depicted as if it was flowing, or even transparent. I will be for sure revisiting this magnificent building, as I am positive there was so much more that I missed in the sheer volume of beautiful artistry on display.

David Hockney has always been one of the modern contemporary artists who stood out to me and is arguably one of the most influential British artists, draughtsman, printmaker, stage designer and photographer of the 20th century.

In 1953, at 16 years old, Hockney was admitted to the Bradford College of Art (1953-57) where he studied traditional painting and life drawing. Then, he was admitted to the Royal College of Art, London (1959–62) where the graphic styles he discovered laid the foundation for his later works.

Pop art emerged in the UK in the 1950s and aimed to blur the boundaries between fine art and more popular commercial images of strong visual impact and vibrant colour. It was also during this period that Hockney made the move to start a new life in California. In the 1960s he became an important contributor to the pop art movement, depicting scenes and influences from his own personal life.

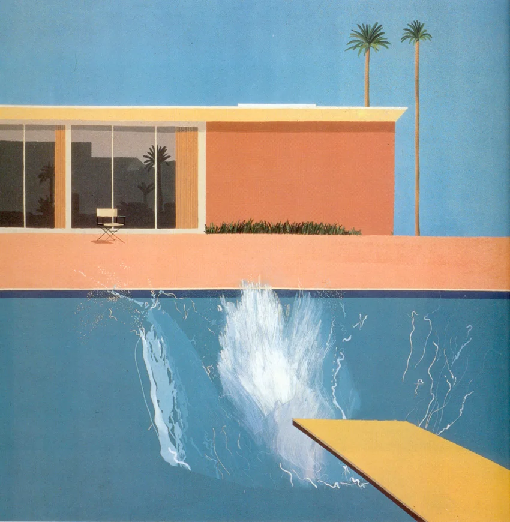

My first introduction to Hockney’s works was the 1967 painting, The Bigger Splash, which was a result of two smaller paintings, A Little Splash and The Splash, both created in 1966. The painting freezes a moment in time as the water droplets are suspended in the air. It is the clean lines, flat areas of colour and clear fresh light with little to no shadows, that for me is a signature of Hockney’s works.

In 2005, after more than half a century away, Hockney returned to live in Yorkshire and has since been artistically influenced by the English countryside. Notably the winding roads, trees, hedge lined country lanes, and undulating hills which he has painted many times over the years.

Hockney would often create many of his large pieces in as many as 30-50 panels to make up a larger image to be viewed as one piece. One of his largest pieces measuring 15 x 40ft the Bigger Trees Near Warter, was created over 5 weeks for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in June 2007. The 50 separate panels feature coppiced trees in early spring, 30 of which were shadowed by one large sycamore tree.

Not one to be restricted by being bound to a single style or medium, Hockney’s works have varied over 6 decades. He explores a broad range of subjects and different influences, and quickly picked up the new medium of acrylic paint, in the 1960s. He has continued to explore different mediums such as collages, photomontage, photography, and even digital art.

The use of stained or coloured glass has a long history, even being used by the ancient Egyptians and Romans. It has been put to a variety of uses, from small objects and windows, to impressive large-scale windows used in important buildings, churches, and monasteries. It was seen as an important part of religious story telling in times when many were illiterate. The decorative panels would tell stories from the Bible, and revered the saints, monarchs, and other important historical figures. These stunningly colourful windows provided much needed light into the dark interiors of the churches.

With a history spanning more than 1000 years, stained glass used in windows has been a key feature in many significant religious buildings, and many of these wonderful creations remain today. Fine examples of early medieval stained glass can be seen throughout Europe, and some of the earliest examples remain in Chartre cathedral in France, with more than 80% of the original glazing remaining including one of the rose windows.

Very little medieval stained glass now remains in Westminster Abbey, but there are other good examples of glass from the 18th century remaining elsewhere in the present day. A few fragments of 13th century medieval glass, showing fragments of painted faces, written texts, and coats of arms, are on display in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee gallery.

Sadly, during the reformation in the 16th century, many of these beautiful windows were smashed and replaced with clear glass. It was not until the 19th century that a renewed interest in the traditional techniques of stained glass that many windows in churches were restored. In several cases the clear glass was replaced with elaborate stained windows depicting biblical scenes.

Due to present techniques removing the use of lead, we can now have beautiful stained-glass creations in our own homes. In the past, the manufacture of clear glass was expensive, but coloured, stained, or painted glass was even more so, as it required highly skilled artisans who utilised the art of alchemy to create colour and fuse patterns and texture into the glass.

It takes many different techniques to create a singular window. Flat colour is made by heating silica sand to high temperatures and, while it is still in a molten state, metal oxides are added to the crucible to give the glass its beautiful colour. Bright colours could be created from metal oxides such as cobalt for blue, manganese for purple, antimony for yellow and iron or copper oxide for green, and gold for a red. However, gold was very expensive, and copper would begin to be more commonly used to create the red colour.

Introduced in the 14th century, a silver compound was applied to the back of clear glass and once this had been heated, the silver stain penetrated the glass leaving a yellow-orange coloured glass and that’s where the term where stained glass came from!

Glass was then blown and lengthened into a cylindrical shape. The ends were cut off, the cylinder cut up the long edge and while the glass was still hot and pliable, the cylinder was flattened. Using this technique creates different variations of the same colour, by applying shapes from different sheets of the same colour glass creates different tones. Altering the way in which the glass was heated and cooled would produce even greater tonal variations.

The later Middle Ages saw the development of the craft taken to a heightened level, and many new

techniques were used to create the glass panels.

During the 15th century, a technique called Grisaille stained-glass was made popular. This monochrome technique can often be seen in the finer details of the painted faces and hands.

A mixture of powdered glass and iron filings were mixed to create a black paint, with a binder such as oil or gum Arabic, which could be brushed on to larger areas of the glass, for lines, texture, and details. The paint was then fused to the glass in a kiln. This technique could be used over clear glass, or more commonly over a transparent yellow stained glass.

Designs were sketched out into working drawings known as cartoons, showing the outline of each individual piece which were then cut, held in place with lead strips and soldered together creating a whole panel. Glazing cement was then added on both sides of the panel to make it waterproof. To make sure the cement hardened, chalk mixture called whitening was added over the panel and left to harden over a few days. To create a more stable structure many panels are used in the creation of one window.

I was so inspired by my trip to Westminster Abbey I just had to have a go at making my own ‘stained-glass window’ using Pebeo Cerne Relief and Pinata Alcohol Inks. This is my depiction of Newark, I’ve included recognisable and significant landmarks to the area. You can watch a sped-up version of me creating my stained-glass window on YouTube. Don’t forget to share it with us if you have a go yourself!

I was so inspired by my trip to Westminster Abbey I just had to have a go at making my own ‘stained-glass window’ using Pebeo Cerne Relief and Pinata Alcohol Inks. This is my depiction of Newark, I’ve included recognisable and significant landmarks to the area. You can watch a sped-up version of me creating my stained-glass window on YouTube. Don’t forget to share it with us if you have a go yourself!

Notifications