If planning a trip to London, UK I will often take an earlier train, in order to have a few hours to pop into the British Library which is a stone’s throw from Kings Cross and St Pancras train stations. Alongside the books and journals of some of the greatest writers over the centuries there are the illuminated manuscripts which I am always in awe of the beautiful, illuminated pages from around the world, dating from the 5th century to 1600, in brightly coloured pigments and burnished gold or silver leaf to enhance and illuminate the text.

The word Manuscript comes from the Latin words for “written by hand” and illumination from the Latin for “enlighten” or “lit up.” Dating back as early as the 5th century the practice of illumination, or adding decoration to manuscripts, was a skill of beautifying hand-copied texts and scriptures. At least one or more of the illuminated pages must contain metal usually gold or silver leaf or it to be considered as an illuminated text. It was as complex and costly process reserved for important texts, usually religious in content for Church alter Bibles, Royalty and the very wealthy who wanted to process one of these much-treasured texts. This continued throughout the Middle Ages with more demand for classical works or scientific text, the art form began to decline with the introduction of the printing press in the mid-15th century where multiple volumes could be created quickly.

The description of Illuminated texts is used to refer predominantly European texts. The practice of creating illuminated texts followed a similar technique in Islamic, Mesoamerican and far Eastern traditions but these are more commonly referred to as painted.

Creating a luminated text involved a painstakingly long process from the preparation of the support, usually vellum or parchment or even papyrus (but these did not survive well) and paper supports which began to be used in Europe during the 12th century. Up to the 12th century, most manuscripts were produced in monasteries by monks, with the early texts being created by one person for the multiple processes needed when illuminating a text, in a dedicated area called a scriptorium. By the 14th century demand had increased for these text secular scribes were employed within the monastery. Later texts involved numerous specialists working on different sections. Pages were pre-prepared and planned to ensure everything fitted on the page and agreement on style and content for each page. A scribe creates the text using a quill made for goose or swan feathers and black ink, a second monk referred to as a Rubicator would proofread and add the blue and red title, headlines or initials. Illustrator would paint the illustrations and gilding using leaves of gold or silver would be added. These pages were then bound into a book known as a Codex.

The artist’s colour palette was surprisingly wide and varied with pigment and dyes being sourced from animals, minerals, plants, and insects as well as more unusual and interesting ingredients and the powdered pigments were blended with water and egg white or gum Arabic and in some cases substances such as urine and earwax were used to prepare pigments.

Reds -the intense reds were extracted from insects: carmine (cochineal), crimson or Lac- a scarlet colour or minerals such as Vermillion, rust and

Blues – obtained from minerals such as lapis lazuli, azurite and Smalt, obtained by grinding blue glass and Indigo a plant-based dye.

Greens – malachite a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, Terre Verte a greyish-green pigment made from a kind of clay (glauconite) and China Green, extracted form Buckthorn berries.

Yellows – sourced from Earth minerals like Ochre, Orpiment an orange-yellow arsenic sulfide crystal, or plant-based dyes such as Saffron, Turmeric and Weld

Browns – Burnt Umber

Whites – lead white

Blacks – vine charcoal, Carbon black from burnt bones,

It was from this tradition that the intricate Invitations for the Coronation of Charles III on 6th May 2023 at Westminster Abby, were designed by heraldic artist Andrew Jamieson. The original design was hand-painted with intricate details in watercolour and gouache and the ornately illustrated invitations printed on recycled paper recycled card with gold foil detailing. The invites are bursting with intricate details and symbolism representing King Charles’s interest in plants and natural history and environmental campaigning intertwined with the four flowers of the Four countries of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, the red and white Tudor Rose, Daffodil, Thistle and Shamrock.

Andrew Jamieson is one of a few fully trained practitioners in the world, of the ancient and specialist art of manuscript illumination and heraldic design. The Art Workers Guild, of which King Charles is and Honorary member, put forward 8 artists to submit rough designs for the historic invite and Jamieson’s design was chosen.

The invite has the Royal coat of arms of King Charles and Queen Consort, officially to become Queen Camilla at the coronation, in each or the top corners. The other stand-out feature is the British folklore image of the Green man, an ancient figure is often seen carved in medieval English churches as a human face with branches and foliage growing out of the mouth. It is thought to represent rebirth to celebrate the new reign of King Charles III. Surrounded by Ivy, Hawthorn and Oak leaves and the national flowers of the United Kingdom.

I have used my printed-off copy of the invite to study the intricate details, as unfortunately my invite must have been lost in the post!

Each time you look at the beautifully painted images you see something new both real and symbolic.

Each of the top corners contains the heraldic coat of arms for King Charles and Queen Camilla and in surrounding borders there are additional images of the three animals representing coat of arms. On the left border, the Lion from both coats of arms, in the right board the unicorn from King Charles and the Blue Boar from Queen Camilla’s coat of arms, all with bright red tongues sticking out of their mouths. The little blue boar sitting in the bottom left corner was one of the first animals I spotted.

Working around the borders, which are full of British wildflowers, there is something new each time and I have had fun trying to identify each different plant.

In the top border there is a large, gilded C and on this sit a Robin and a Wren. One of the symbolisms for both these bold little birds is rebirth but often as messengers from lost loved ones.

Situated in the left and right borders are 3 insects: a bee fully laden with pollen, a Ladybird and a common Blue Butterfly. Three is an important reference throughout the borders as it represents that King Charles is the third King with that name. The symbol three has many meanings spiritual and mystic throughout folklore, stories, science and religion.

The Green man motif takes pride of place in the centre of the bottom border, crowned with an acorn and surrounded by the four national flowers this is the most symmetrical image and continues symmetrically along the whole of the bottom border. It is from this from which all the other images burst from in an array of detail and colour reminding me of a wild meadow. I have mentioned the three animals, the two birds and the four national flowers but here are the other flowers I have identified. In the top border, Granny’s Bonnet, Violets, Lily of the valley, Daisy, Cowslip, Pinks, Wild Strawberries, Forget me nots and sprigs of hawthorn. The left border has a sprig of Rosemary, Daffodil, Thistle, Snowdrops, Shamrock, Dog rose, Tudor Rose, Forget me nots and finally the right border contains, Bluebells, Thistle, daffodil, Forget me nots, Cornflowers, Daffodil, Shamrock, Wild Pansy, Primroses, Tudor Rose and Thistle. In addition, there are tiny sprigs of greenery and blue, white and red flowers (unidentified by me) and dots of gold gilding throughout the board which enhances and ties in with the regal gilding in the coats of arms, and the inner boards.

The pairing of the Forget Me Nots rich in symbolism and lore commonly as a symbol of remembrance and one in each border could be nod a to loved ones no longer around.

Full of symbolism the Coronation invite will still hold its little secrets but stand as a beautiful testament of skills of the artist Andrew Jamieson.

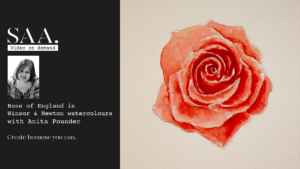

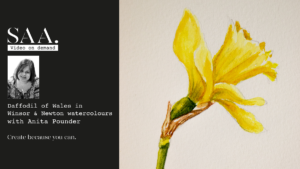

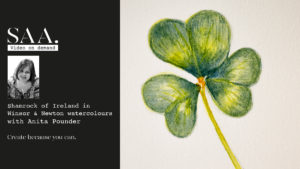

Explore our video selection of inspiration for the four flowers of the Four countries of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, the red and white Tudor Rose, Daffodil, Thistle and Shamrock.

Watch Anita Pounder – Rose of England in Winsor & Newton Watercolours

Watch Anita Pounder – Daffodil of Wales in Winsor & Newton Watercolours

Watch Anita Pounder – Thistle of Scotland in Winsor & Newton Watercolours

Watch Anita Pounder – Shamrock of Ireland in Winsor & Newton Watercolours

Sources:

The Coronation of His Majesty The King | The Royal Family

Twelve Greatest Illuminated Manuscripts – World History Encyclopedia

The British Library – The British Library (bl.uk)